100 Years of The Kiplinger Letter: Centenary Special Edition

On September 29, 1923, the very first Kiplinger Letter was published.

This week, instead of forecasting what’s ahead, allow us to look back on the past century of the Letter: How it began, the events it chronicled, who started it, how it evolved over the years and how each issue gets produced now. (Get a free issue of The Kiplinger Letter or subscribe).

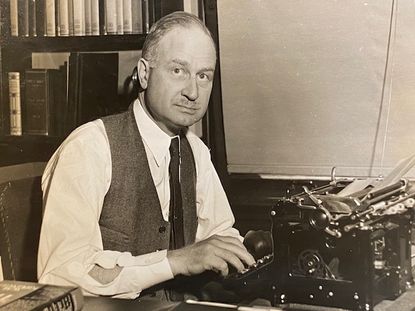

Willard Monroe Kiplinger

The father of the new Letter, W. M. Kiplinger, a journalist from Ohio born in 1891, came to Washington to cover the Treasury Department for the Associated Press during World War I. He developed deep sources in government and gained a knack for discounting official statements and seeing the actual government policies.

He began his own service in 1920, alerting banks and other clients to issues in Washington that affected them, using his reporting savvy and judgment. His weekly bulletin proved popular, so he decided to sell it as a stand-alone periodical.

Sign up for Kiplinger’s Free E-Newsletters

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice on investing, taxes, retirement, personal finance and more - straight to your e-mail.

Profit and prosper with the best of expert advice - straight to your e-mail.

The first Letter was mailed in 1923 to 500 prospects, with an offer of 52 issues for $10 ($180 in today’s dollars). All through the 1920s, the Letter slowly gained subscribers, then soared in the 1930s, when Kiplinger’s network of government sources allowed him to guide a disoriented business community through the New Deal.

Read a copy of the original Letter and then let’s take a look back at some Letter forecasts over the decades, to see what it covered and what it had to say at the time as great events unfolded.

The Letter: The Early Years

The Stock Market: “We would give you bullish reports if we could find any, but we can’t.” November 12, 1928, less than a year before the market crash of 1929

“Authorities, who keep an indirect eye on the stock market, speak freely of ‘the dangerously high position of the stock market.’” January 14, 1929

“The drift toward government control over private business operations will proceed more rapidly. Economic laws will not be permitted to operate normally. New political experiments will be adopted to modify normal economic operations.” December 24, 1932, with Franklin D. Roosevelt set to take office on March 4, 1933

“Ultimate war: If official opinions could be reduced to betting odds, they would be 2-to-1 against war within the next year, but 3-to-1 for war within the next five years. No one tries to say where, when or why.” July 28, 1934

“U.S. would keep out of the war, directly, for a considerable time. Seems probable that it would take nearly two years to create circumstances which MIGHT draw us into war as belligerent.” September 17, 1938

Bluntly, we are entering a preparation-for-war era.

November 26, 1938

“Bluntly, we are entering a preparation-for-war era.” November 26, 1938

“The United States in 1940 will not get into the shooting war, but WILL become more firmly committed to the side of Britain-and-France.” December 23, 1939

“War with Japan? Officials simply did not know, but their cautious private observations indicated that they are prepared for the worst.” December 6, 1941

“Invasion across the Channel: Preparations are in the final stage.” January 1, 1944

“Cities of Japan are going to be destroyed in a few months. Our bomber force is sufficient to reduce them to rubble like Berlin, but faster and worse, due to ‘technological improvements’ in bombing.” June 2, 1945

The Letter: Post-War

“Now it’s ‘two worlds’, openly hostile without even a pretense of friendly collaboration. Every move everywhere is toward a showdown. This means, within the coming year, an intensification of the ‘Cold War.’ At times, on the fringes, it will be a ‘hot war’ in danger of spreading.” December 20, 1947

“New crisis with Russia is imminent in Berlin.” June 5, 1948

“All of China is headed toward communist control.” April 23, 1949

“Korea is a fringe war for us, and [Vietnam] may become another. No U.S. troops to [Vietnam], but much more air and naval help; ships, airplanes and maybe men to train pilots for which the U.S. pays. Thus the U.S. will have to spread its strength out further and thinner.” June 7, 1952

“Future demand for housing is shown by marriages, plus incomes. Another big boom, starting in the early 1960s, is almost sure. The wave of births in the past 15 years will become a wave of marriages then, creating demand for millions of homes — a bigger boom than at present.” December 24, 1954

What about all this talk of going to the moon, and first? It sounds fantastic, but scientists [...] tell us it can be done.

October 12, 1957

“What about all this talk of going to the moon, and first? It sounds fantastic, but scientists who seem to have feet on the ground tell us it can be done.” October 12, 1957

“What’s Kennedy going to do about Cuba? NOTHING. He’s in a box. Thus Cuba is a communist armed camp and will remain so indefinitely.” March 17, 1962

“As for Vietnam, we’ll eventually step aside there, after making a big military push to strengthen our hand for negotiations, compromise. The truth is, we can’t win. We can only fuzz the outcome to save face.” January 24, 1964

“Civil rights bill will pass the Senate, probably sometime in May. Southerners can NOT block it, as some think.” February 28, 1964

“Now about November: Landslide for Nixon? Entirely possible, but a scandal might queer it and the Republicans are very edgy about charges that some fund-raising activities weren’t on the up and up; and bugging of the Democrats’ headquarters. They hope the smell won’t get too strong.” August 25, 1972

“Microchips: The leading edge of technology for years to come.” December 28, 1979.

“Fiber optics, glass replicating copper wire, a major innovation in communications is about to take off and will boost capacity enormously.” May 23, 1980

“It’s not just an election, it’s a turning point. A veer to the right nationwide, away from the ‘new liberalism’ that has dominated.” November 7, 1980, on Reagan’s election

“The stock market generally has been in a slump for many years — an extended trough. Prices are up only slightly from the earlier lows. Ten years hence, today’s prices will seem like bargains, which they are.” December 26, 1980, Dow at 964

“Strains in Poland may lead to deeper cracks in the Soviet bloc.” September 9, 1988

“It’s clear that the Western democracies have won the Cold War. But no one really knows what will follow or the effects on us.” October 13, 1989

“What to do about the menace of Iraq’s army and nuclear potential? How to make sure sparks that remain don’t cause new troubles? We won’t be able to walk away with an attitude of ‘that’s that.’” January 11, 1991

“Fight against terrorism will likely crimp U.S. civil liberties. Americans must decide on trade-offs of privacy and security.” September 12, 2001

“Yes, some clouds loom on the horizon for the U.S. economy: Soaring housing prices, with the risk of a bursting bubble.” July 22, 2005

“All this may sound bleak. But don’t lose sight of the positive factors. The financial system is sound and the economy was in good shape before the virus hit. Any recession, while potentially severe, should be fairly short.” March 13, 2020

The Letter: Elections

While we don’t think of it as our primary job as editors of the Letter, our presidential election forecasts always garner considerable attention. We’ve called every race going back to Coolidge in 1924, ignoring personal preferences and weighing each contest coolly and objectively. Generally, that’s served us well. But... we have two famous, or infamous, bad calls:

Dewey in 1948

Many readers likely recall our 2016 forecast, but almost no one remembers 1948. In the latter, we were sure Truman would lose, that we said so confidently, and repeatedly. When it proved wrong, W. M. Kiplinger wrote a whole special issue apologizing and analyzing how we went wrong. The short version: Despite a lot of reporting, we missed a last-minute shift to Truman during the campaign’s final days.

Clinton in 2016

In 2016, we were not sure Clinton would defeat Trump. We saw a path for Trump and outlined how he could win, but said it was unlikely he could win all the key states. To nearly everyone’s surprise, he did. Previously accurate polls missed his support.

The lesson: Every election is a nail-biter for forecasters. Some seem easy in hindsight, but none are easy in real-time. Each one makes us sweat. Sometimes, subtle shifts in the electorate are hard to spot.

We’ve gone 23-for-25 in our history, but those two we missed are a constant reminder not to take anything for granted.

The Letter: Crises

Two of the darkest issues ever of the Letter covered presidential deaths: Franklin Roosevelt in 1945 and John Kennedy in 1963. You may be interested in what the Letter wrote at those moments of national grief and uncertainty.

On FDR’s death: “President Truman is not seasoned for his huge responsibilities, and he would admit it, for he is a modest and genuine man. But Truman is no dummy, he has courage, and he can’t be pushed around. Under him, the country will not go to the dogs.

One fact about Truman is that he has a deep sense of DUTY. He doesn’t talk about it much, but those who work with him always notice that when he makes up his mind as to what his duty is, he is bullheaded, and often overrides considerations of temporary political expediency.”

On Kennedy’s death: In 1963, the Letter was already written on a Friday afternoon in November, until the news from Dallas required a rewrite about the new president, Lyndon Johnson:

“President Kennedy was a young man in the affairs of the world. He survived a war only to lose his life in time of peace. He showed courage in his job and gave his life in the line of duty. But the government must, and does, go on.

Now a new president. What kind of man? What kind of president? Essentially a doer rather than a thinker. He follows through by insisting on daily reports from his staff on what they have done, whom they have talked to, what they found out, the outcome of it all.

He runs things with a tight rein. His role with Congress will be quite obvious and quite firm. There will be no mistake about who is head of the Democratic Party and all the party members will know it.”

In 1973, not about a presidential death, but a presidency in crisis:

“Impeach Nixon? Still remote, but a growing possibility. House started the preliminary investigation which can lead to that. Leaders think an impeachment fever may be building up in the country. Might he resign? Yes, if the case against him is overpowering, or if he decides the country has turned its back on him, guilty or not.” October 26, 1973

The Letter: Our Work

Perhaps you’d like to know a bit about how we produce the Letter, and who writes it. The editors have always been anonymous, and rightly so, but here’s a little about our process and who does this work for you each week.

The staff is small: Eight editors, not counting our editor emeritus, Knight Kiplinger — W. M. Kiplinger’s grandson, who still advises us on every issue. Some of us are professional journalists. Others, experts in various fields, such as taxes and economics, who started out in other industries and then came to the Letter.

We each have our various beats, and each editor is trusted to decide what topics and events are important to cover. Some are major news stories that we know readers are wondering about. Others, not in the news, but important in our view — things we believe readers should know about and will find useful.

We meet each Friday morning, to discuss the coming issue’s lead story and other important topics we are following. This is informal and collegial. Editors swap ideas, debate forecasts and challenge each other’s analysis (in a friendly way).

The goal: To sift a lot of information and arrive at the best possible forecast, distilled into a few words and clearly stated, to save readers’ time. Ideally, we strive to be helpful on a wide range of subjects, something for everyone in each issue, we hope.

After our meeting, we consult a wide range of sources — members of Congress, businesspeople, economists, and lots of data from the government and elsewhere. Oftentimes, what we hear or find is murky, or contradictory. We try to dig deep, make judgments about what’s accurate or significant, what to discount and how to explain all this.

A few editors write each issue, in our unique style, akin to how it was done by W. M. Kiplinger himself but evolved to change with the times — our signature “voice.”

When forecasting, we always give realistic prospects, as we see them. Not the merits of what we expect to happen. Our own personal feelings don’t matter when it comes to the Letter. We aspire to be accurate and useful for readers, regardless of how we feel about any particular prediction we make. Or, for that matter, how readers may feel.

Our own feelings don’t matter when it comes to the Letter.

Jim Patterson

We know we often deliver unwanted news. We don’t like doing it, but we have always felt it to be our duty, to equip our clients with the most accurate outlook possible, and let them decide how to feel about it.

But, we have a few biases.

We are, broadly speaking, pro-America and we want the country to prosper, to be at peace domestically and abroad, as much as possible regardless of who is president, or who controls Congress.

We are, generally, an optimistic bunch. No rose-colored glasses here, but the Letter’s experience over the past century has mostly justified optimism about the future, especially America’s future. When times are tough, as they often are, we look for hopeful signs. We have found that doom and gloom is often overdone.

Most of all, we are biased in favor of you and your success, your businesses and your own personal fortunes. We aim to be helpful, always. We know it’s difficult running a business or managing your financial affairs. We are always looking for information we can share to make your tasks a little easier, and we are honored to do so.

After turning 100, is the Letter slowing down, getting tired? Not at all. We relish the challenge of trying to make sense of the world each week. We intend to keep at it for a good long time to come. We’ll use new technologies as they emerge, perhaps branch out into new formats, but our mission won’t change: To serve our readers, as best we can.

Thanks to you for letting us do that each week, you and all our readers over the decades. As always, let us know how we can help.

The Kiplinger Letter, is a collection of concise weekly forecasts on business and economic trends, as well as what to expect from Washington, to help you understand what’s coming up to make the most of your investments and your money. Subscribe to The Kiplinger Letter.

Jim joined Kiplinger in December 2010, covering energy and commodities markets, autos, environment and sports business for The Kiplinger Letter. He is now the managing editor of The Kiplinger Letter and The Kiplinger Tax Letter. He also frequently appears on radio and podcasts to discuss the outlook for gasoline prices and new car technologies. Prior to joining Kiplinger, he covered federal grant funding and congressional appropriations for Thompson Publishing Group, writing for a range of print and online publications. He holds a BA in history from the University of Rochester.

-

-

The Era of Super-Low Interest Rates Could Be Over: The Kiplinger Letter

The Era of Super-Low Interest Rates Could Be Over: The Kiplinger LetterThe Kiplinger Letter We’re likely never going back to the historically low rates that prevailed in late 2019 and early 2020.

By David Payne Published

-

The Simple Yet Devastatingly Effective Secret To Warren Buffett and Oprah's Success

The Simple Yet Devastatingly Effective Secret To Warren Buffett and Oprah's SuccessA look at the common lesson to learn from the success of Warren Buffett and Oprah Winfrey.

By Eric McLoyd Published

-

Work Email Phishing Scams on the Rise: The Kiplinger Letter

Work Email Phishing Scams on the Rise: The Kiplinger LetterThe Kiplinger Letter Phishing scam emails continue to plague companies despite utilizing powerful email security tools.

By John Miley Published

-

Tech Giants Look to Curb AI's Energy Demands: The Kiplinger Letter

Tech Giants Look to Curb AI's Energy Demands: The Kiplinger LetterThe Kiplinger Letter The expansion in AI is pushing tech giants to explore new ways to reduce energy use, while also providing energy transparency.

By John Miley Published

-

New Employment Guidance Proposed on Hostile Work Practices: The Kiplinger Letter

New Employment Guidance Proposed on Hostile Work Practices: The Kiplinger LetterThe Kiplinger Letter New guidelines for employers fueled by a sharp increase in employment discrimination lawsuits in 2023.

By Matthew Housiaux Published

-

SEC Cracks Down on Misleading Fund Names: The Kiplinger Letter

SEC Cracks Down on Misleading Fund Names: The Kiplinger LetterThe Kiplinger Letter The SEC rules aim to crack down on so-called “greenwashing” — misleading or deceptive claims by funds that use ESG factors.

By Rodrigo Sermeño Published

-

As Tensions Rise, U.S. Imports From China Shrink: The Kiplinger Letter

As Tensions Rise, U.S. Imports From China Shrink: The Kiplinger LetterThe Kiplinger Letter China now accounts for less than 13.5% of American imports from abroad.

By Rodrigo Sermeño Published

-

Traffic Circles Can Make Intersections Safer, But Also Confusing: The Kiplinger Letter

Traffic Circles Can Make Intersections Safer, But Also Confusing: The Kiplinger LetterThe Kiplinger Letter In the U.S. traffic circles are on the rise — studies show that roundabouts, as they are commonly known, are safer than traditional intersections.

By Sean Lengell Published

-

Cargo Thefts on the Rise: The Kiplinger Letter

Cargo Thefts on the Rise: The Kiplinger LetterThe Kiplinger Letter Organized crime rings are targeting goods in shipments.

By David Payne Published

-

What the Charter, Disney Pay TV Battle Means for the Industry: The Kiplinger Letter

What the Charter, Disney Pay TV Battle Means for the Industry: The Kiplinger LetterThe Kiplinger Letter Charter called the pay TV model 'broken', during its battle with Disney. Is this a turning point for the television industry?

By John Miley Published